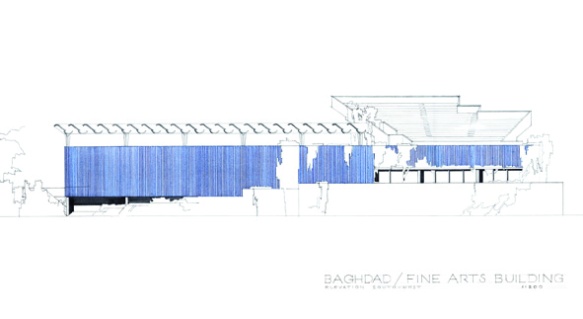

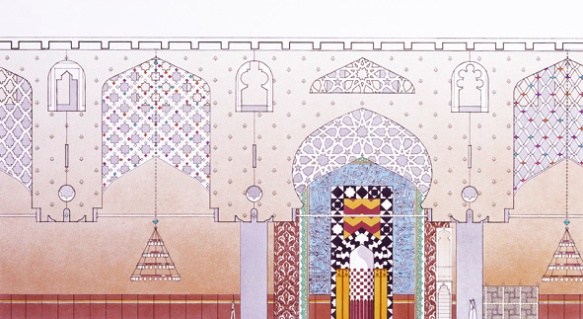

Alvar and Aino Aalto, Project for the Fine Arts Museum of Baghdad within the Civic Center, 1957-1963, Baghdad, Iraq. Image courtesy of Col·legi d´Arquitectes de Catalunya (COAC)

Last spring I saw a show of modernist architectural plans for Baghdad in the 1950s at the Center for Architecture in New York. I tried to cover the exhibition, but I caught it too late to make it timely. Now, home for the holidays, I came across the show again; it’s traveled up to the Boston Society of Architects.

From the curators:

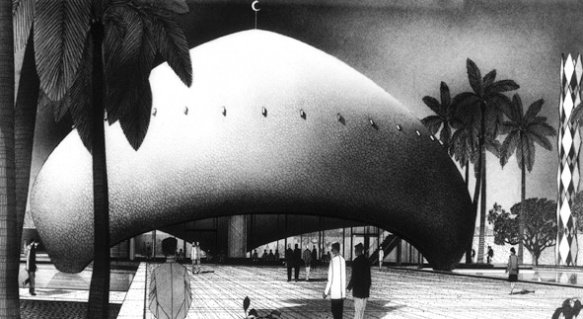

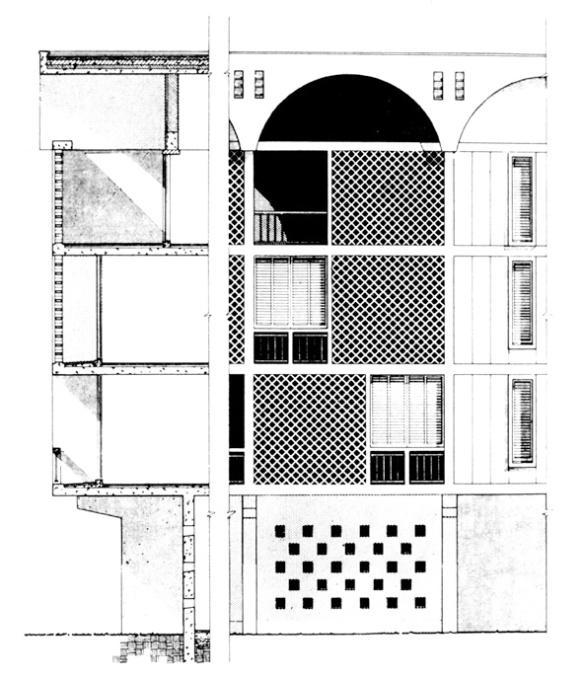

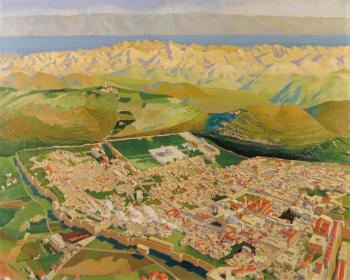

City of Mirages: Baghdad, 1952–1982 presents built and unbuilt work by 11 architects, including Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Josep Lluís Sert, Alvar and Aino Aalto, and Robert Venturi FAIA. Models of various scales of the built and unbuilt work by these and other architects are accompanied by a large-scale model of Baghdad.

The history of modern architecture in Baghdad is not well known and remains relatively underexplored. Specialists in Iraq and in exile throughout the world have undertaken detailed analyses of the topic, but many of the studies have been difficult to access in Europe and the United States, and the destruction of war has made it impossible to recover the complete modernist record of Iraq. The exhibition describes an era in which Baghdad was a thriving, cosmopolitan city, and when an ambitious program of modernization led to proposals and built work by leading international architects.

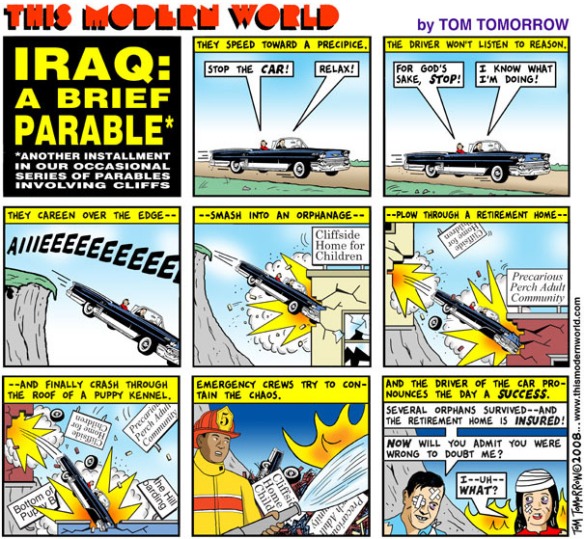

The show is really about speculative modernist architecture and unbuilt urban plans in the Middle East. Frank Lloyd Wright in Baghdad? Oscar Niemeyer in Tripoli? The latter was recently brought up in the International Herald Tribune, on the occasion both of Niemeyer’s death at 104 and Syria’s war spilling over the border into Lebanon. I wrote a similar, but more personal piece in The National in 2010, reflecting on a visit to Niemeyer’s unfinished fairground in northern Lebanon. That piece included some thoughts on Baghdad:

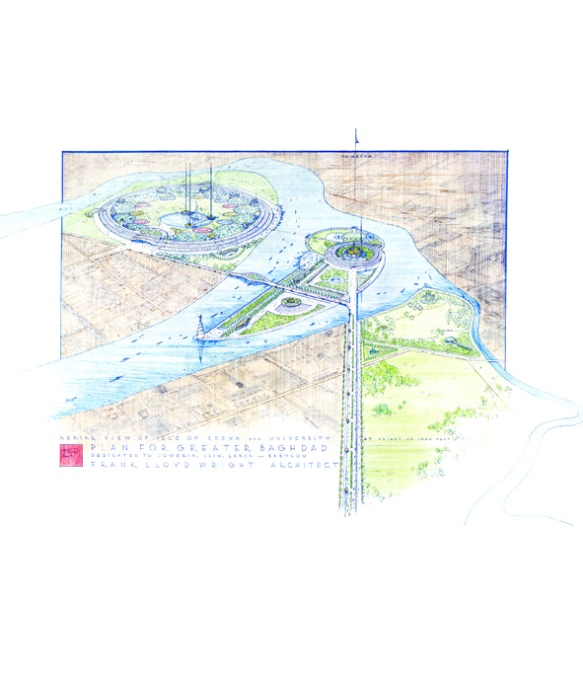

As we left Niemeyer’s park at dusk, the guard was gladly opening the gate for a wedding party in a black Mercedes SUV. They had come to take photos with the sunset. Against which concrete background we did not know. The pyramid? The Lebanese pavilion? The arch? Earlier, standing below the arch, following the uneven bend of one side, I didn’t think of Lebanon. As a visitor from Cairo, I thought about other cities in the region a half-century ago that looked to modernism to stage their national and urban aspirations. A few years before Lebanese bureaucrats were consulting with Niemeyer on what he imagined would “become for Tripoli a centre of attraction, of cultural interest, artistically and recreationally of the greatest importance with its theatres, museums, athletic and leisure centres”, Frank Lloyd Wright visited Iraq at the behest of King Faisal II, who sought a Western architectural remaking of his capital not unlike Dubai and Abu Dhabi today.

But Wright’s sweeping development for “Greater Baghdad” was never built. The coup leaders who killed Faisal II and his family at their palace in the summer of 1958 also killed Wright’s overblown plan for a university, museums, opera house and an outsized statue of Harun al Rashid at the tip of an island in the Tigris that Wright had renamed Edena. Wright died anyway the next year. Walter Gropius – who, unlike Wright, was affixed to cubic modernism of the International style – was selected by the new government to build the new University of Baghdad in a suburb outside the city centre. Le Corbusier worked on a sports complex until his death in 1965. Sixteen years later, a version of his gymnasium finally opened, named after Saddam Hussein.

One of the themes of City of Mirages is that these plans and buildings, so many of them unrealized, represent the city’s and state’s bygone cosmopolitanism. Sometimes that word elicits groans, if the nostalgia is misplaced, like the Alexandria imagined and memorialized by Lawrence Durrell. But the show doesn’t long for the days of monarchy, even if Wright’s plans, along with Gropius’s and Corbusier’s, were commissioned by the king on the eve of his brutal, bloody overthrow. The models and plans are their own kind of artifacts — even if the models were reconstructed by architectural students in Spain — of a city whose recent urban history is about destruction, and not development.

Artifacts ran through the late, great Anthony Shadid’s fantastic essay in Granta last year on Baghdad College, a prep school for Iraqi boys founded by American Jesuits in 1932. The school was shut down by the Baathist government in the late 1960s. Shadid’s essay excavates the history of American missionaries in Baghdad in decades when America had a decidedly different role and presence in the Middle East. The title, appropriately, was “The American Age, Iraq.” “A moment has been lost, and that’s what I was trying to write about: an intersection that we did once see between America and Iraq and an idealized vision both had of the other,” Shadid said in an interview about the piece. Here here is talking about it on NPR.

I had this passage in mind as I looked over drawings and models of an unrealized modernist dream for Iraq’s capital.

Unlike Beirut or, closer to home, Fallujah, Baghdad was never destroyed by its war. The city here feels more like an eclipsed imperial capital, abandoned, neglected and dominated by the ageing fortifications of its futile defence against the forces that had overwhelmed it. Think of medieval Rome. An acquaintance once described all this refuse of war as athar, Arabic for artefacts, and I thought of the word as I drove down the road to Baghdad College, past piles of charred trash, to see a teacher there.

Walter Gropius, TAC (The Architects’ Collaborative) and Hisham A. Munir, University of Baghdad Campus, 1957-, Baghdad, Iraq. Image courtesy of Col·legi d´Arquitectes de Catalunya (COAC)

José Luis Sert, The U.S. Embassy, Baghdad, 1955-1959, Baghdad, Iraq. Image courtesy of Col·legi d´Arquitectes de Catalunya (COAC)

Frank Lloyd Wright, Plan for a Greater Baghdad, 1957-1959, Baghdad, Iraq. Image courtesy of Col·legi d´Arquitectes de Catalunya (COAC)

Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown, Project for the Competition for a National Mosque of Baghdad, 1982, Baghdad, Iraq. Image Credit: Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc.