This is a story I wrote from Damascus in 2009, during the year I lived in Syria. It originally appeared in Wunderkammer Magazine: http://www.wunderkammermag.com/politics-and-society/iraq-refugee-syria

They lived well in Baghdad; their eldest daughter had two cars. Six years later, the Iraqi couple moves their mattresses out of the bedroom each night to sleep on the living room floor. The only bedroom is left for their daughters while they live in this concrete refugee suburb of Damascus.

It was Friday and quiet on the balcony above the street. The fried fish lunch was over and the mother was reading fortunes in the bottom of coffee cups. The father skulked past the couch and flashed his pack of cigarettes. He didn’t smoke before the war. He was a chain-smoker by the time he arrived in Damascus. He shrugged when his wife explained his new habit—“he’s always with a cigarette, always, but he never smoked before.” She brought her index and middle finger to her mouth and mimed puff after puff.

The father talked of his construction company in Baghdad. “We sold huge pistons for Caterpillars and other large machines,” he explained. “I can know just by putting my ear to the gears or the engine if it’s working well or not,” he grinned behind his cigarette. “I’m very clever.”

A few weeks later in their living room, the table was cleared for a gorging of rice, grilled fish, kibbeh stuffed with egg, and salad eaten by plucking the cheese-draped lettuce from the bowl by hand. The family’s hospitality is typical of Syria, but their food is much better.

A wealthy Christian family, they became refugees when Shia militias began enforcing a fanaticism of piety in Baghdad’s streets and thieves started roaming their neighborhood. Their son’s fatal kidnapping and a younger daughter’s death drove them to Damascus.

“But we are here,” he said, as he always said in response to his wife’s war stories. “We are here, with new friends”— he calls us, two Americans, his children, extending an amount of kindness that circumstance should have blunted— “so thank God.”

Then he launched into jokes, spurred by the dessert of sugary cardamom tea and date cookies covered in sesame seeds. With the help of his wife, he explained Uday Hussein’s speech impediment and its lethal effect on the players of the Rashid Football Club. Saddam’s elder son meant to say “congratulations” to his players after a big win, but what came out was a command to line them all up to be shot. And we heard of the man from Ramadi, a contestant on Who Wants To Be A Millionaire, who was asked to name the color of his wife’s underwear and needed a life-line: “Can I phone a friend?”

The last joke they told involved the church. A pauper goes to the alter every week, but instead of dropping a few coins in the donation box, he asks the Virgin Mary, the baby Jesus in her arms, if it’s alright if he takes the money. She always says yes. Eventually the priest grows suspicious, until one day he waits behind the statue for the pauper, who arrives and pleads his usual request, expecting the same silent consent.

“No!” comes a male voice in response.

“Shh!” the pauper replies. “I’m not stealing from you! Just your mother!”

They could joke about Iraq as they sat in their small one bedroom apartment, the television on in the background showing American cooking shows and Dr. Phil. They are another once-prosperous family from Iraq displaced in Syria.

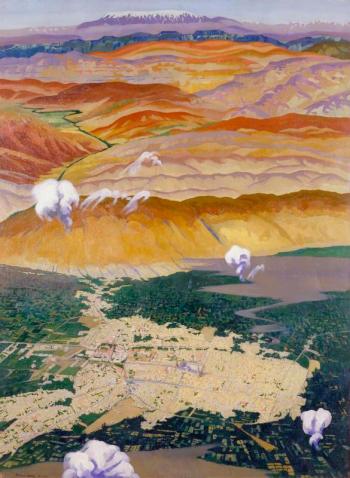

The country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs counts 1.2 million Iraqis living here with valid visas, designating them “Arab guests and visitors.” The number of illegal residents is unknown but pushes the total number above 1.5 million, as Syria has hosted the bulk Iraq’s refugees. In the fall of 2007, the government effectively closed its borders, though many refugees still arrive, including a wave of hundreds of Christians who fled violence in Mosul last fall. There is a slow trickle of Iraqis returning home, mostly for financial reasons: they cannot legally work in Syria and, when the money runs out, going back is the only option.

The insistence on eating helping after helping of grilled fish – “Iraqi food combines all the spices of Indian, Persian, and Turkish food,” the eldest daughter said – and the seemingly endless amount of family jokes reveal what the fall of Baghdad, the occupation, sectarianism, and callous American adventurism cannot erase: a sense of humor, of food, of hospitality and humanity that go widely unreported in so many stories from Iraq and its new diaspora.

“When Saddam’s statue fell, I knew Iraq was finished,” the father said. Weeks earlier, on the balcony after the fish lunch talking about his pistons, he said emphatically that he was not a Ba’athist.

That same afternoon the mother talked about an old friend who was Sunni. “We were in university together,” she said. “Our children were schoolmates.” Then, after Saddam fell and the occupation worsened, “all of sudden, she was speaking of me as a Christian and she as a Muslim. She started scolding relatives – an uncle and his niece – for kissing when they greeted each other in an apartment. ‘A man and woman should not kiss like that,’ she would say.” The mother stirred her tea with force. “This is crazy.”

Before the table had been set for dinner and bowl after bowl of salad and rice and fish had been placed on the folding table before the couch, the father’s phone rang as we finished a game of chess. A friend had just gotten the call from the United Nations and was going be resettled in America. They all cheered congratulations, and the father blessed his friend on the phone.

Then he turned back to the chessboard. We were playing slowly, smoking cigarette after cigarette, barely speaking. His daughter sat next to him and was whispering strategies. “Come on Fredo, move!” he said. He told me he had loved playing chess in Baghdad, though it was hard for me to imagine him sitting in a café there, over a chessboard like this, and not smoking. But I easily imagined him playing with his son while his third and youngest daughter whispered her own strategies in his ear.

I looked through the haze and down at the ashtray and pictured their smoke-free house in Baghdad and unlimited games of chess. Then he took a long drag and, exhaling, made a move and put me in checkmate.